At the beginning of my real estate career, I spent a couple of years in a traditional real estate office starting in 2018, where the main goal was selling as much as possible. It was transactional and narrow—reinforcing the same systems that continue to cause harm politically, environmentally, and socially. Coming from a background in regenerative agriculture and historic craftsmanship, I found the culture in most real estate offices surprisingly shallow. They were filled with wonderful people, but with a mission to serve the bottom line—one that, in real estate, often leads to specific and widespread negative outcomes, which I began tracking more and more. I even have my very first (and very stale) headshot from 2019—no white hairs in my beard yet. I’ll include it here for a little throwback laugh

By 2020, I had learned the mechanics of how real estate works—and was eventually white-knuckling my way through it. The conversations that felt important to me kept falling flat in my real estate office. I was burned, and bummed out. That’s when I started sensing a need for another way forward.

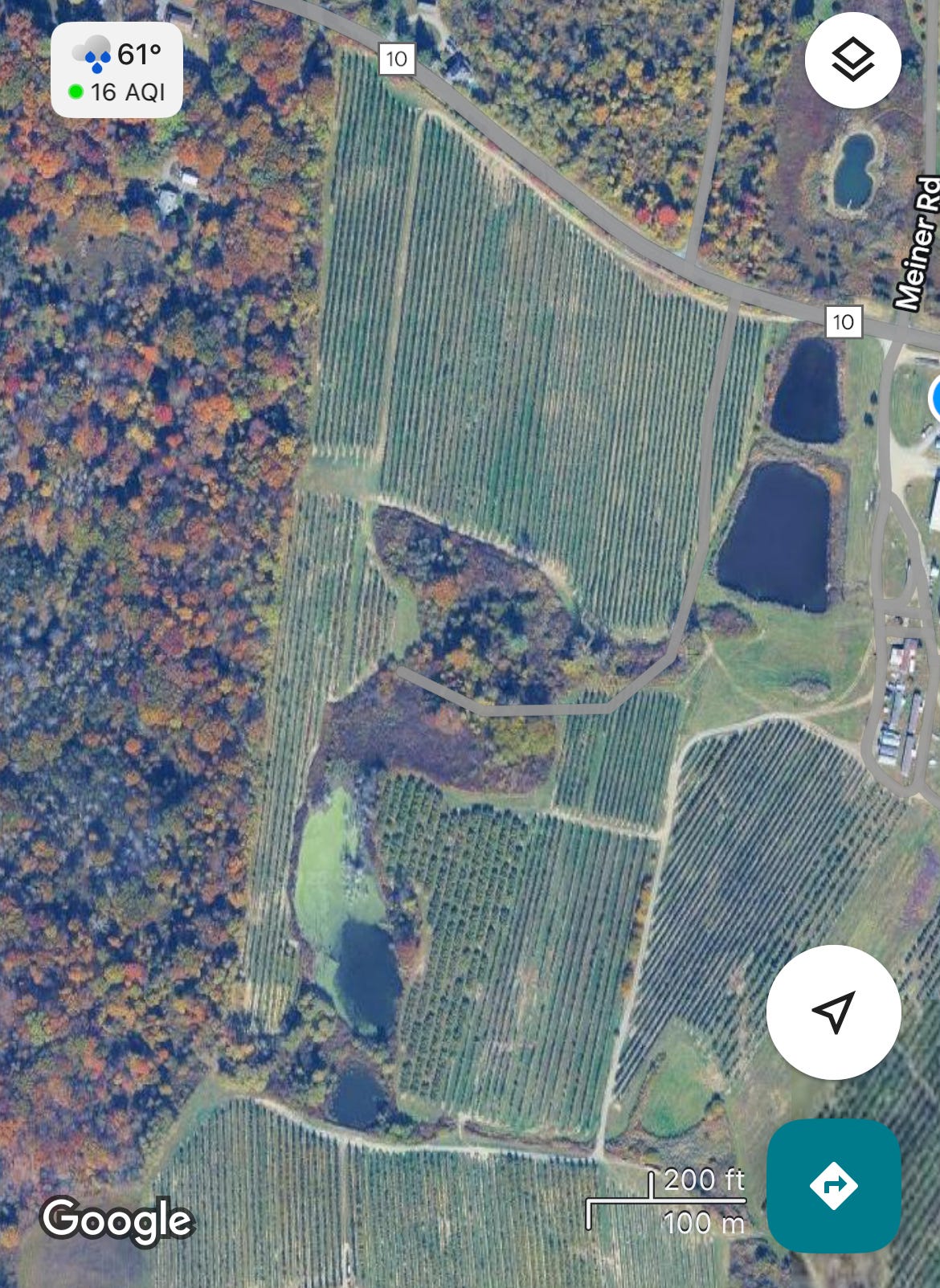

One place stood out—an old orchard near where I was living. I drove by it all the time. A lot of people do.

I started thinking about it seriously that same year. It felt like more than just a property—it held so many overlapping tensions I kept seeing but rarely heard named out loud: ecological damage, stalled land transitions, worker exploitation/immigrant labor, housing decay, the limitations of conservation easements, and market dynamics that leave places like this behind. Layered into all of that is a long and unresolved racial history—who’s been allowed to own land, who’s worked it under harsh conditions, and who’s been systematically excluded from the benefits. This orchard carried all those contradictions at once.

At the time, my focus was really just on this orchard. I wasn’t trying to make a statement about the region. I just kept returning to this one place. It felt like something I could rally energy around. A way to gather people, test ideas, and see if a different kind of future for land was possible—starting right here.

I first talked about it with a close friend, then shared it with the Hudson Incubator, a local entrepreneurship group. I wasn’t totally sure what I wanted to do. But I began using the orchard as a kind of case study—an example of how regenerative thinking and real estate might be brought together to approach land differently.

Then the pandemic hit. Everything went online. And in that strange stillness, I started meeting people who were asking similar questions online and nationally—about land, housing, ecology, and what might come after the systems we’ve relied on begin to crack.

That’s when I connected with the team behind Latitude. Over the next few years, we built language, relationships, and a small but committed community around those ideas. We helped others find their way into the conversation, too.

I’ve since stepped away from Latitude. These days, my work is more local—closer to home in the Hudson Valley, more hands-on. And five years later, that same orchard that first inspired my thinking continues to poke at me.

Over the years, I’ve toured the orchard many times. I’ve seen different realtors list it on Zillow, met with some of them along the way. I even got proactive and helped coalesce a group of neighbors to collectively make an offer. For various specific and good reasons—which I won’t go into—it didn’t move forward.

On paper, it checks a few important boxes: strong location, visibility, steady car traffic. But it’s tangled.

There’s a conservation easement on the property—a two-sided sword. It gave the farmer a much-needed cash infusion and ensures the land stays in agriculture in perpetuity, which sounds great in theory. But in practice, these easements can be overly rigid. They rarely make room for nuance around how agriculture is practiced. There’s little distinction between chemical-intensive monoculture and regenerative land stewardship. That rigidity can make it hard to evolve a place like this into something more sustainable, more adaptive, more community-serving. That being said, I still admire most easements and believe they’ve been—and still are—critical in protecting landscapes and farmland.

The worker housing on the orchard is in rough shape. The farmhouse is historic and beautiful but falling apart—still a ripe candidate for historic tax credits. The apples are part of a long-standing monoculture, grown with pesticides in depleted soil. Reversing that degradation will take time and intention. It's easily one of the biggest conundrums in the scenario.

The original farmer is no longer able to care for the land. Some of it has already been subdivided and sold. A few old apple trees still hang on between houses. And unlike vegetable CSAs or flower farms, young farmers aren’t lining up to take over orchards. The next chapter here isn’t obvious.

Then earlier this year, after basically letting the place drift from my attention, I got a few texts. Someone was asking about that orchard again. Around the same time, I heard about another one just up the road—same story: declining trees, shuttered infrastructure, a seller ready to move on.

I toured that second orchard with a realtor, who quickly passed me off to the owner—a farmer who walked me through the property and showed me parcels that had been sold off, areas they hoped luxury housing might be built, and barns they no longer knew what to do with. An apple economy I knew little about suddenly felt like something I was being asked to help with. And the questions I’d been sitting with came rushing back. Who’s going to take on these kinds of places? What happens when no one does?

Now, there are some glimmers—orchards taking new steps. Stone Ridge Orchard and Rose Hill come to mind. But the majority of the industry still feels stuck.

I don’t have answers—just a growing sense that something obvious is being missed. And I’m back here again, pointing at it.

I still care about places like this. Our region’s identity is rooted in them. These orchards helped shape the Hudson Valley—and the Big Apple too. I think they matter. I think we can do something different with them.

I’m interested in what comes next for these orchards specifically, and medium-sized farms more broadly. Maybe it’s reinventing perennial systems, agroecology, integrating housing in smarter, 21st-century ways. Maybe it’s something we haven’t fully named yet.

I’ve started doing some light, pointed outreach, and I’d love to hear from others thinking seriously about orchard health, land transitions, or rural/housing regeneration in our region. If you have ideas, leads, connections—or know of any grant opportunities that could support this kind of work—I’m all ears.

If you’re involved in grantmaking, land conservation, rural development, or community-scale housing, I’d especially love to connect. This kind of work takes time, partnership, and real support—and I’m currently looking for all three.

And I’ll admit: I’m a little exhausted. I’m still learning to appreciate the long arc of time these kinds of topics and transitions require. This work can feel like a thorn in my side. But it also holds real potential. I still believe it could help unwind and reverse a trajectory that’s unhealthy for our region—and begin to introduce its opposite

Thats it for now, till soon..

So cool to hear your story. So sad with all the millions and billions floating around this world something regenerative can’t happen. I wonder if it’s due to our individual/collective scarcity mindset. Thank you for sharing this vision the seeds of which might grow.

Also what is the machinery in the last photo?

You're on to something Daniel--if you could manifest a breakthrough with one orchard, it could spread to others in similar situations... keep at it! (--: